2008 Household Survey of Public Participation in the Arts

- Research

- Open Access

- Published:

Who engages in the arts in the United States? A comparing of several types of appointment using information from The Full general Social Survey

BMC Public Wellness volume 21, Article number:1349 (2021) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Background

Engaging in the arts is a health-related behavior that may be influenced by social inequalities. While it is more often than not accepted that in that location is a social gradient in traditional arts and cultural activities, such as attending classical music performances and museums, previous studies of arts date in the The states have not adequately investigated whether similar demographic and socioeconomic factors are related to other forms of arts engagement.

Methods

Using cantankerous-sectional data from the Full general Social Survey (GSS) in the US, we examined which demographic, socioeconomic, residential, and wellness factors were associated with omnipresence at arts events, participation in arts activities, membership of creative groups, and being interested in (but not attending) arts events. We combined data from 1993 to 2016 in 4 belittling samples with a sample size of 8684 for arts events, 4372 for arts activities, 4268 for creative groups, and 2061 for interested non-attendees. Data were analysed using logistic regression.

Results

More education was associated with increased levels of all types of arts engagement. Parental pedagogy demonstrated a similar association. Existence female person, compared to male person, was as well consistently associated with higher levels of engagement. Omnipresence at arts events was lower in participants with lower income and social form, poorer health, and those living in less urban areas. However, these factors were non associated with participation in arts activities or creative groups or beingness an interested not-attendee.

Conclusions

Overall, nosotros constitute testify for a social gradient in attendance at arts events, which was not as pronounced in participation in arts activities or creative groups or interest in arts events. Given the many benefits of date in the arts for educational activity, health, and wider welfare, our findings demonstrate the importance of identifying factors to reduce barriers to participation in the arts across all groups in society.

Background

There are many known social inequalities in health, including differences in good for you life expectancy and bloodshed [one, 2]. These disparities may be partially explained past a social slope in a diverseness of health behaviors, including diet, obesity, concrete action, alcohol consumption, and smoking [3,4,5]. Wellness behavior norms may exist learnt inside the socioeconomic context, with social determinants influencing behavior throughout the life course [6]. Engaging in the arts is an case of a wellness-related behavior that demonstrates social inequalities [7, 8].

Arts appointment typically refers to unlike types of creative activity, from actively participating in the arts (e.yard. dancing, singing, acting, painting, reading) to more receptive cultural engagement (e.g. going to museums, galleries, exhibits, performances and the theater [9]). It can besides comprehend broader artistic activities that, whilst not always labelled as 'arts', share similar properties of creative skill and imagination (e.one thousand. gardening, cooking, and hobby or book groups [10]). In 2019, the World Health Organization identified more 3000 studies showing the benign touch on of arts engagement on mental and physical health and social determinants of health, from didactics to social cohesion and welfare [9]. Despite growing awareness of the benefits of engaging with the arts, in that location is a social gradient in arts participation. Previous surveys take found that arts engagement in the Us (US) may differ according to socioeconomic status, education, and income [11,12,13]. Similar factors are associated with inequalities in access to health care and health and social outcomes [14,15,16,17]. Varying date in the arts may therefore further contribute to wellness and social inequalities [8]. However, the literature on this topic is limited past a number of factors.

Showtime, many previous studies have focused on certain demographic or socioeconomic predictors of arts engagement without e'er taking into account the broad range of factors that may be related to i another. From these studies, the most consistent predictors of increased arts engagement are higher levels of education and income [12, 13, xviii,19,xx,21,22,23,24]. There have been extensive efforts to differentiate the effects of teaching and income on arts appointment, and it appears that both independently contribute to date levels [21, 25]. Nevertheless, teaching may exist more strongly associated with attending highbrow cultural events, whereas income is more than strongly associated with other forms of arts date [25]. Further, self-identified social course may be another important factor which should exist studied alongside income and pedagogy [23]. There is also show for lower rates of date in Black than White racial/indigenous groups [12, xviii, 22, 26, 27]. Still, it remains unclear whether race/ethnicity has a strong clan with date later other factors, particularly education and income (equally interconnected systems that contribute to structural racism), have been taken into business relationship [18, 21, 22, 27, 28].

Additionally, there are other factors that could be associated with arts appointment that have non been investigated in the The states to date. In the United kingdom, at that place are geographical differences in participation independent of individual demographic and socio-economic backgrounds [29]. Farther, living alone is associated with fewer perceived opportunities to appoint in the arts and those with poorer physical and mental health may feel more barriers to engaging [thirty]. As many previous studies of arts engagement in the US are based on the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (SPPA; National Endowment for the Arts), which does not collect data on physical and mental wellness, these factors have not been investigated.

Moreover, in the Usa, most research on predictors of arts date has measured appointment with 'criterion' arts activities, every bit defined in the SPPA. These activities include attention jazz, classical music, opera, musical or non-musical plays, ballet performances, and art museums or art galleries. Although these activities are not intended to be comprehensive [31], they have repeatedly been used equally a metric of engagement in the arts. This has led to the perception that arts participation is failing in the US [11, 22, 32]. Withal, when divers more broadly, including other types of arts activities and going beyond the not-profit sector to recognize the many diverse commercial forms of cultural expression, participation is not declining and the way in which people participate may instead be changing [xiii, 33, 34]. At that place may be a growing gap between arts participation metrics and the means in which people participate, and this could exist affecting our understanding of the predictors of engagement [35].

Therefore, in this study, we used a large nationally representative sample of adults in the U.s. (the Full general Social Survey; GSS) to investigate predictors of dissimilar types of arts appointment. Specifically, nosotros were interested in whether there are social inequalities in appointment in the arts, every bit found in other health-related behaviors. To practise this, we tested which demographic, socioeconomic, residential, and health factors were associated with attendance at arts events, participation in arts activities, and membership of creative groups. Further, in order to differentiate between non-attendance due to a lack of interest versus non-attendance due to barriers or a lack of opportunities, we investigated whether like factors were associated with existence interested in, but non attending, arts events. Finally, nosotros examined whether appointment changed across time, from 1993 to 2016, and whether associations between demographic and socioeconomic factors and date changed over these ii decades.

Methods

Sample

Participants were fatigued from the General Social Survey (GSS); a repeated cross-exclusive and rotating console written report of adults anile 18 and over in the United states of america [36]. Each survey yr was an independently drawn sample of English-speaking individuals living in non-institutional arrangements. From 2006 onwards, Spanish-speakers were added to the target population. Full probability sampling was employed, and surveys sub-sampled non-respondents from 2004 onwards.

Nosotros used data from GSS waves at which arts outcomes were measured between 1993 and 2016. Each moving ridge included a unique sample of individuals so we were able to combine data across waves. We used iv indicators of arts engagement (arts events, arts activities, artistic groups, and interested non-attendees), each measured in dissimilar waves of the GSS. Arts events were measured in 1993, 1998, 2002, 2012 and 2016, arts activities were measured in 1993, 1998, and 2002, creative groups were measured in 1993, 1994, 2004, and 2010, and interested non-attendees were measured in 2012 and 2016. Nosotros therefore identified four samples, ane for each upshot. When combining samples across all relevant years, the total number of participants was 14,890, 7203, 12,311, and 7687 for arts events, activities, creative groups, and interested not-attendees respectively. We then restricted the sample just to participants with complete data on arts variables, which produced a terminal sample size of 8684 for arts events, 4372 for arts activities, 4268 for artistic groups, and 2061 for interested non-attendees (run into Supplementary Table 1 for further details).

All participants gave informed consent and this study has Institutional Review Board approving from the University of Florida (IRB201901792) and ethical approval from University College London Enquiry Ethics Committee (project 18839/001).

Arts engagement outcomes

Arts events

Participants were asked whether they had attended arts events in the concluding 12 months, not including school performances. In 1993, attendance at 3 events was measured as the following: a) fine art museum or gallery, b) ballet or trip the light fantastic toe performance, and c) classical music or opera performance. In 1998 and 2002, two additional events were added to this list: d) popular music functioning, and due east) non-musical stage play performance. In 2012 and 2016, attendance at 2 types of event was measured; a) music, theatre, or dance functioning, and b) art exhibit (including paintings, sculpture, textiles, graphic pattern, or photography). Due to these differences in measurement beyond years, we complanate all responses into a binary variable indicating attendance at any event in the concluding 12 months (0 = none, 1 = one or more). As this does not entirely account for the changes in question manner, we tested whether the changing definition of arts events altered our findings in sensitivity analyses (outlined below). For total details of the questions asked in each wave, encounter Supplementary Table 2.

Arts activities

Participants self-reported whether they participated in any kind of arts activity in the final 12 months, including: a) making art or craft objects, b) taking function in music, trip the light fantastic, or theatrical performance, and c) playing a musical instrument (Supplementary Table two). This was coded equally a binary variable (0 = none, 1 = one or more than), and was measured consistently in 1993, 1998, and 2002.

Artistic groups

Participants were asked nigh the groups or organizations of which they were a fellow member in 1993, 1994, 2004, and 2010. The creative groups were hobby or garden clubs and literary, art, discussion, or study groups (Supplementary Table 2). A binary variable was created indicating membership in either of these group types (0 = none, 1 = one or more than).

Interested non-attendees

In the 2012 and 2016 GSS, participants who responded to the arts event questions were besides asked if there was an arts event during the final 12 months that they had wanted to go to but did not attend (0 = no, 1 = yes). In 2012, only participants who had non attended an issue during the last 12 months were asked this question. In 2016, all participants who were asked about arts consequence attendance were also asked whether at that place was an event that they had wanted to go to only did non attend. As we aimed to include only participants who were interested non-attendees, nosotros excluded those who reported attending an arts issue in 2016 (northward = 738 excluded).

Exposures

Nosotros examined whether a range of demographic, socioeconomic, residential, and wellness factors were associated with arts engagement. Demographics included age (years), sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (White, Black, or Other) and marital status (married, separated/divorced/widowed, or never married). Socioeconomic factors included full number of years of education (0–20 years), parental years of education (highest reported maternal or paternal didactics; 0–xx years), employment status in the terminal week (employed, unemployed or not currently working, retired, keeping business firm, or other), family income in constant dollars (base = 1986; $0 to $9999, $10,000 to $nineteen,999, $20,000 to $29,999, $30,000 to $49,999, or $50,000+), subjective satisfaction with financial situation (non satisfied at all, more or less satisfied, or pretty well satisfied), and a subjective rating of social class (lower class, working class, middle class, or upper class).

Residential factors included level of urbanicity (medium to big city with 50,000 people or more than; suburb of a medium to large urban center; unincorporated expanse of a medium to large city; modest city, town or hamlet of 2500 to 50,000 people; and smaller areas or open country), number of people living in the household (i–10), and whether there was an area within a mile of their home where they would be afraid to walk alone at night (yep or no).

Finally, we included a general health rating (first-class, good, fair, or poor).

Statistical analyses

Nosotros used four logistic regression models to test cantankerous-sectional associations between demographic, socioeconomic, residential, and wellness exposures and binary arts engagement outcomes. Each outcome (arts events, arts activities, creative groups, interested not-attendees) was modelled separately. Where there was testify of a non-linear clan between age and arts appointment, we included a quadratic age term. Equally a number of like exposures were included, multicollinearity was assessed to ensure that Variance Inflation Factors were less than ten [37]. All analyses were weighted to account for the sub-sampling of non-respondents and the number of adults in the household using weights supplied by the GSS [36]. We accounted for clustering of participants within main sampling units by using robust standard errors.

We also tested whether there was any evidence that associations between arts engagement outcomes and age, race/ethnicity, class, income, and sex differed over time. Nosotros included an interaction term between each exposure and survey year in separate logistic regression models. Where in that location was evidence for an interaction, we then examined the clan between the exposure and arts appointment separately in each survey yr.

For participants with missing data on exposures, we imputed data using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE [38]). Nosotros used linear, logistic, ordinal, and multinomial regression and predictive mean matching according to variable blazon, generating 50 imputed data sets (maximum missing data ranged from 10 to 35% in each sample; Supplementary Table three). The imputation model included all variables used in analyses, auxiliary variables, and the survey weights. Auxiliary variables were separate election group, interviewer's rating of the respondent's attitude toward the interview and agreement of questions, respondent's rating of their family income (relative to other Americans), and geographic mobility since age 16. Imputations were performed separately according to survey year. For artistic groups, several exposures (satisfaction with financial situation, full general health rating, and feeling afraid in neighborhood) and an auxiliary variable (relative income) were missing for all participants in some years and so were not included in the imputations or analyses. All other variables were successfully imputed. The results of analyses did non vary betwixt consummate cases and imputed data sets (Supplementary Table iv), so findings from the imputed data are reported. All analyses were performed using Stata 16 [39].

Sensitivity assay

We tested whether the changing definition of arts event attendance altered our findings. In this assay, we used the most homogenous measures of arts events, those included from 1998 to 2016. We therefore repeated the primary analysis excluding participants from 1993 (which used a narrower definition of arts events) and examined whether similar factors were associated with arts outcome attendance in this subsample (n = 7094; Supplementary Tabular array vii).

Results

Arts events

In total, 8684 participants provided data on attendance at arts events, 53% of whom were female and 78% were White (Table 1). These participants ranged in historic period from 18 to 89 years, with a mean age of 46.6 (SD = 17.0). Overall, 56% had attended an arts event in the concluding 12 months, although this varied beyond years (1993: 48%, 1998: 62%, 2002: 66%, 2012: 46%, 2016: 50%).

In the logistic regression model, there was show for associations betwixt several demographic factors and attending arts events (Table ii). Females had 24% higher odds (95% CI = 1.ten–ane.39) of attendance than males. In comparison to White participants, Black participants had 34% lower odds (95% CI = 0.55–0.78) of attendance. Participants who had never been married had 37% higher odds (95% CI = 1.xiv–ane.63) of attendance than those who were married.

There was evidence that several socioeconomic factors were associated with omnipresence. Compared to those with a family unit income of less than $10,000, participants in all other income groups had higher odds of omnipresence. The highest odds were in the highest income grouping. Subjective rating of social class was as well associated with attendance, with higher classes associated with increasing odds. Each additional twelvemonth of education was associated with i.19 times higher odds (95% CI = 1.xvi–1.22) of attendance. Parental instruction was similarly associated with increased odds of omnipresence, although the estimated odds ratio was smaller (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = ane.04–1.07).

Two residential factors were associated with attendance. Compared to those living in medium to large cities, the odds of attendance reduced with decreasing level of urbanicity. The odds of omnipresence were lowest in smaller areas or open up state. Additionally, for each additional person in the household, participants had 5% lower odds (95% CI = 0.xc–0.99) of attendance. Participants who rated their health as fair (OR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.56–0.83) or poor (OR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.33–0.66) had lower odds of attention events than participants who rated their health as first-class.

Finally, the results suggested that event attendance varied beyond survey years, although in that location was no articulate fourth dimension trend. In comparing to 1993, the odds of attendance were college in 1998, 2002, and 2012 only did not differ in 2016.

Arts activities

Overall, 4372 individuals reported whether they had participated in arts activities. These individuals ranged in age from eighteen to 89 years, with a mean age of 44.viii (SD = 17.0). Almost 53% were female and 81% were White (Table one). On boilerplate, 54% reported participating in at least one arts action in the last 12 months, and this was relatively stable beyond time (1993: 55%, 1998: 51%, 2002: 55%).

Fewer factors were associated with participation in arts activities than with attendance at arts events (Table ii). Females had 1.71 times higher odds (95% CI = 1.45–two.00) of participating than males. Both Black (OR = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.38–0.61) and individuals of Other races/ethnicities (OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.51–0.96) were less likely to report participating than those who were White. Individuals who were unemployed or not working had higher odds of participating than those working (OR = ane.44, 95% CI = 1.06–1.95). Equally with attending arts events, increased years of educational activity (OR = one.08, 95% CI = ane.05–ane.12) and parental education (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = i.02–1.07) were both associated with higher odds of participating in arts activities. At that place was no evidence that any other factors were associated with participation.

Creative groups

Membership of artistic groups was reported by 4268 participants, who were similar demographically to participants who reported other arts outcomes (Table 1). Membership in creative groups was lower than omnipresence at events or participation in activities. Overall, xix% of participants reported being a fellow member of a creative group, and this may have decreased over fourth dimension (1993: 20%, 1994: xvi%, 2004: 18%, 2010: 17%).

Despite a lower proportion of participants beingness members of creative groups, membership was associated with similar factors to arts activities (Table two). Females had i.33 times college odds (95% CI = one.08–1.63) of membership than males. There was too evidence that the odds of membership increased with more educational activity (OR = 1.xv, 95% CI = one.10–1.20) and parental teaching (OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 1.01–1.08). In contrast to arts activities, those who were never married had ane.58 times higher odds (95% CI = ane.18–ii.eleven) of membership than married participants and the odds of membership increased with historic period (OR = 1.01, 95% CI = ane.00–1.02). Finally, there was testify that membership decreased over time, with the odds decreasing by 32% (95% CI = 0.54–0.87) from 1993 to 2010.

Interested not-attendees

Overall, 2061 participants reported whether there was an arts event that they had wanted to get to but did not attend, 29% of whom were interested not-attendees. The proportion of interested non-attendees remained consistent across years (2012: 29%, 2016: thirty%).

As with attendance at arts events, there was evidence that beingness an interested not-attendee was associated with race/ethnicity and years of education (Tabular array ii). Other races/ethnicities had lower odds of being an interested not-attendee than White individuals (OR = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.35–0.89), and the odds of interested non-attendance increased with level of education (OR = ane.11, 95% CI = 1.05–1.17). However, in dissimilarity to event attendance, those who were more than or less satisfied with their financial situation had lower odds of existence an interested non-attendee than those who were not satisfied at all (OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.52–0.96). There was no bear witness that being an interested non-attendee was associated with gender, marital status, employment status, family income, social class, parental pedagogy, level of urbanicity, household size, or general health rating.

Change across survey years

Next, we tested whether associations between arts appointment outcomes and historic period, sex, race/ethnicity, class, and income differed over time. In that location was no evidence for interactions between survey year and any exposures on participation in arts activities, membership of creative groups, or being an interested non-attendee (Supplementary Table 5). There was also no prove for interactions between survey year and age, class, or income on arts event attendance.

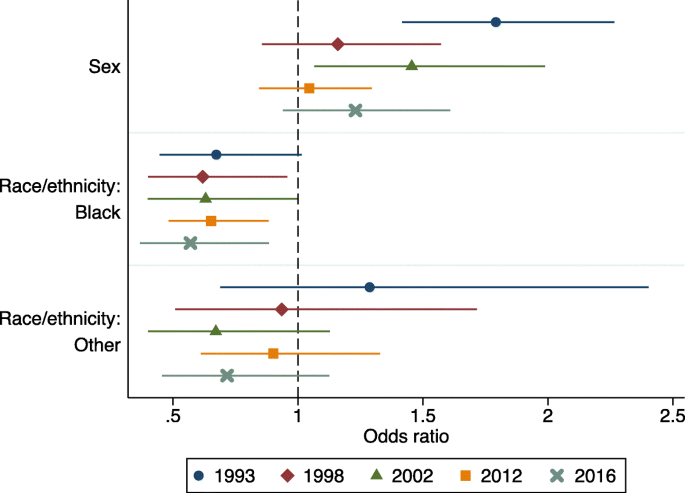

All the same, in that location was bear witness for an interaction between survey twelvemonth and sexual activity on event attendance. There was no linear fourth dimension trend, equally females had college odds of omnipresence than males in 1993 and 2002 but there were no sex differences in other survey years (Fig. one; Supplementary Tabular array half dozen). At that place was also bear witness for an interaction between survey year and race/ethnicity on issue attendance. Black participants had lower odds of attending than White participants, and this difference increased over fourth dimension (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table half-dozen).

Results of subgroup analyses, with logistic regression models testing associations between exposures and the odds of attention arts events separately in each survey year (1993 due north = 1590, 1998 n = 1432, 2002 n = 1355, 2012 north = 2838, 2016 n = 1469). Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are displayed. For associations betwixt sex and arts events, the odds ratio represents attendance in females compared to males. For associations between race/ethnicity and arts events, White is the reference category. Associations were estimated in the total logistic regression models (including all exposures as shown in Table 2), but just results for sex and race/ethnicity are presented

Sensitivity analyses

We have reported findings based on imputed data simply the results of analyses did not vary when limited to complete cases, as shown in Supplementary Table 4. In our sensitivity analysis, limiting the sample to the most homogenous definitions of arts event attendance (i.e. excluding participants from 1993) did non essentially alter our findings (Supplementary Table 7).

Give-and-take

In this study, we examined whether there are social inequalities in engagement in the arts, equally found in other wellness-related behaviors [3,4,v]. Between 1993 and 2016, approximately half of our sample reported attention arts events, and a similar proportion participated in arts activities. In the smaller sample of individuals who completed the GSS in 2012 and 2016, another one third were interested non-attendees, who had been interested in attending an outcome in the last yr simply had not gone to information technology. Fewer people were members of creative groups, with approximately one fifth of the sample between 1993 and 2010 reporting grouping membership. Several demographic factors were consistently associated with date in the arts. For example, engagement was higher in females than males, and married individuals were less likely to appoint than those who had never married. Attendance at arts events and participation in arts activities also differed according to race/ethnicity, although creative group membership did not. Socioeconomic factors showed mixed associations with the unlike types of arts engagement. Higher levels of education and parental education were consistently associated with all types of engagement. Omnipresence at arts events was also associated with higher income and social class, amend health, and living in more urban areas. However, beingness an interested non-attendee of arts events was not associated with these factors. In contrast to arts events, we establish no show that income, social class, wellness, or urbanicity were associated with participation in arts activities and groups. Most of our findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating that a number of demographic and socioeconomic factors are associated with engagement in the arts [13]. Our findings further advance previous inquiry by using a broader definition of arts to more accurately reflect the breadth of appointment in the U.s.a..

The associations between several demographic factors, such as sexual activity and marital status, and engagement in all forms of the arts are consistent with previous evidence [xix, twoscore,41,42,43,44]. We as well plant that race/ethnicity was more strongly associated with participation in arts activities than events, as shown previously [22]. This clan was independent of socioeconomic factors, then is unlikely to be explained by over-representation of indigenous minorities in lower socioeconomic status groups [45]. A study that also used GSS data found that lower attendance at arts events by racial/ethnic minorities may be a effect of barriers such as being unable to get to the venue and not having anyone to go with [23]. These individuals were too more likely to state celebrating their cultural heritage every bit a reason for attending events than those who were White [23, 46]. Nonetheless, in this study, we found that Other races/ethnicities were also less probable to exist interested not-attendees of arts events than White individuals. Although this could be a result of the manner in which arts events were defined (limited to music, theatre, or dance performances or art exhibits), it may also point that some ethnic/racial groups are less interested in attending arts events. A lack of cultural equity, cultural relevance, interest, and inequalities in access are therefore likely to contribute to the racial/indigenous differences in arts appointment.

Overall, our findings support previous evidence that teaching is almost strongly associated with engagement in the arts [12, 13, eighteen,19,xx,21,22,23,24]. However, contrary to some contempo evidence, we did non find that education was more strongly associated with attention events than other forms of arts engagement [25]. Education may increase engagement by helping to cultivate cultural tastes and preferences, raising awareness of activities, and increasing cerebral capacity to engage [47]. Arts education specifically may besides contribute to this association, as it is strongly related to both level of education and arts engagement [20, 27, 32, 48, 49]. We found a similar association with parental education, independent of the individual's own education, although the magnitude of association was smaller. This indicates that childhood socioeconomic condition continues to influence appointment in the arts throughout the lifecourse. Children of parents with more pedagogy may benefit from increased access to the arts during evolution and may be more than probable to receive arts education in childhood (e.g. learning to play an instrument [xxx]). These individuals may therefore have more grooming and experience, enabling them to participate in more highly skilled arts activities (eastward.g. orchestras).

Consistent with previous bear witness for a social gradient in arts engagement, nosotros found that attendance at arts events was less likely with lower income and social class, poorer health, and less urban areas. As being an interested not-attendee was not associated with these factors, they are likely to be barriers specifically to attendance. Individuals across the range of incomes, social classes, health, and levels of urbanicity were interested in attending events at similar rates, just actual attendance differed according to these factors. Previously, individuals with lower household income and social class were more than probable to report barriers to attending events of cost and difficulty of getting to a venue, also every bit a lack of time [23, 46]. Other research has demonstrated that individuals with poorer physical health may experience more barriers affecting their perceived capabilities to engage [30]. Areas that are more urban, such equally cities, are probable to have a larger range of arts events on offer, including at a variety of times and costs as well as appealing to a broader audience, and events may be more geographically dispersed or easier to nourish using public ship. Urbanicity can thus exist interpreted every bit a proxy measure out for the availability of arts events. However, there are also likely to be area-level factors related to the availability and accessibility of the arts that, although not measured in the GSS, require further investigation. In contrast to arts events, we plant no evidence that income, social class, health, or urbanicity were associated with participation in arts activities and groups. These types of engagement may be more than widely available, include more diverse activities, be cheaper to participate in, and oftentimes do not require attendance at a specific venue, which may be hard to reach or not generally attended by certain groups.

There was some mixed show for a social slope in interest in arts events. Individuals with higher levels of education were more than likely to be interested non-attendees, as were people who were more or less satisfied with their financial situation (compared to those who were not satisfied at all). Previous research has suggested that of the unlike types of arts engagement, educational activity is nigh strongly associated with highbrow cultural events [25], which could explicate the association with involvement in events. It is unclear why nosotros institute testify for an association with fiscal satisfaction. Nosotros might conclude that individuals who were satisfied with their fiscal state of affairs were not interested non-attendees because they were financially able to attend whatsoever events of interest, but we found no evidence that financial satisfaction was associated with actual event omnipresence. Additionally, there was no evidence that being an interested non-attendee was associated with income or differed betwixt those who were pretty well satisfied and not at all satisfied with their financial situation. The relationship between interest in the arts, subjective measures of satisfaction with financial situation, and more objective measures of income thus requires farther investigation.

We likewise investigated irresolute patterns of arts date as there has been business concern that arts participation is decreasing in the US [11, 22, 32]. We found some prove that event attendance inverse over fourth dimension, only this was likely a result of changes in the measure of event omnipresence, as there was no linear trend. In contrast, grouping membership decreased over time. Additionally, the racial disparity in event omnipresence, with an over-representation of White individuals compared to those of racial/ethnic minorities, increased from 1993 to 2016. These increasing racial/indigenous inequalities in arts outcome attendance were independent of other socioeconomic factors such equally income and education. All the same, given the nature of structural racism, this finding should be interpreted cautiously and requires replication in studies with consistent measures of event omnipresence. As this study spanned a period of 23 years, with event omnipresence and group membership measured at unlike times, specific social and economical events in each yr could also have contributed to the changing patterns of arts engagement.

Our findings take implications for understanding health and social inequalities in the US. A number of the factors that we take identified as associated with arts engagement are as well associated with inequalities in access to wellness care and health outcomes [fourteen,fifteen,sixteen,17]. This could be considering arts engagement is a correlate of health, with both representing a form of upper-case letter that can be obtained by individuals with more cloth resources, such equally income, and non-material resources, such as social back up [47]. Consequent with this, nosotros found evidence that poorer self-reported wellness was associated with lower attendance at arts events, although it was not associated with interest in attention events or participation in arts activities. Arts engagement could also represent a wellness behaviour that leads to improved wellness outcomes. There is growing show that engagement with the arts can atomic number 82 to a range of health benefits, contained of demographic and socioeconomic factors [9, 50]. It is thus concerning that nosotros have found evidence for differential engagement in the arts. Future enquiry should explore why date is lower in these groups, in particular males, racial/ethnic minorities, and those with lower education. This is particularly of import given that previous efforts to reduce inequalities in access to cultural events by expanding facilities and offer free tickets in Brazil have not been successful [51]. Future research could also investigate whether removing other barriers to engagement, such as providing the arts online to avoid high prices and reduce time constraints, could increase levels of engagement [52]. This could then support the development of interventions to promote date in the arts, and test whether this leads to improvements in health outcomes.

This study has a number of strengths. The GSS was a large nationally representative sample and we included several measures of arts date. Although the GSS has previously been used to report arts engagement [23, 43], inquiry has non generally examined membership of artistic groups in comparing to other forms of date or combined data beyond as many waves of the GSS as in this written report. We tested a range of factors that may be associated with arts engagement, and mutually adjusted for these variables in our models. Using multiple imputation means that missing data should not accept influenced our findings. However, this report also has a number of limitations. We tested cross-sectional associations and thus cannot rule out the possibility of inverse causality. There are some factors, such as wellness, which may have a bidirectional association with arts engagement. Additionally, the GSS did not mensurate attendance at arts events consistently across waves, which is likely to explain the association we found between event omnipresence and survey yr. A broader definition of arts events was used in after years. All the same, when limiting our analyses simply to this broader definition, our findings were consequent. Although our measures of arts engagement were more than inclusive than in many previous studies, they were likely still too narrow. Standard arts engagement questions are non able to capture arts engagement in some immigrant communities [35], and as well typically practice not cover appointment in digital or electronic arts activities such as graphic pattern, photography, film-making, and music product. This could take contributed to our findings of lower arts engagement in individuals who were not White and under-represented arts engagement among younger generations. Time to come inquiry should aim to measure various aspects of arts engagement, peculiarly equally the US moves towards a majority-minority society, in which the not-Hispanic white population will no longer form the majority of the US population [53].

Conclusions

Given the potential importance of engagement in the arts for wellness and wellbeing [ix], individuals should be provided with equal opportunities to participate. Our findings signal that social determinants may influence engagement in the arts throughout the life course. Encouraging arts activities and creative group membership may provide one fashion of widening participation and reducing social inequalities in arts engagement. Information technology will also be of import to recognize that lack of participation may not merely be due to a lack of interest or motivation but may be influenced by structural barriers, such as racism, or a lack of opportunities. Indeed, the nature of many arts activities that take place in well defined arts spaces are rooted in white supremacy, creating a foundational bulwark for Black, Indigeouns and other people of color (BIPOC) groups. Future research is needed to identify what these barriers are and how they can be removed. This is particularly important in the wake of COVID-nineteen, given the closure of many arts venues and the disproportionate effect on BIPOC individuals and those of lower socioeconomic status [28, 54,55,56].

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is bachelor in the GSS repository, https://gss.norc.org/become-the-information/stata.

References

-

Bleich SN, Jarlenski MP, Bong CN, Laveist TA. Health inequalities: trends, progress, and policy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33(1):seven–40. https://doi.org/x.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124658.

-

Zaninotto P, Batty GD, Stenholm Due south, Kawachi I, Hyde Chiliad, Goldberg M, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in disability-costless life expectancy in older people from England and the United States: a cross-national population-based study. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(5):906–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glz266.

-

Stringhini S, Sabia S, Shipley Chiliad, Brunner Eastward, Nabi H, Kivimaki M, et al. Association of socioeconomic position with health behaviors and bloodshed. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;303(12):1159–66. https://doi.org/x.1001/jama.2010.297.

-

Harper S, Lynch J. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in adult wellness behaviors among U.South. states, 1990-2004. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(2):177–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490712200207.

-

Scholes S, Bann D. Pedagogy-related disparities in reported physical activity during leisure-time, active transportation, and piece of work among Us adults: repeated cantankerous-sectional analysis from the National Health and nutrition examination surveys, 2007 to 2016. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5857-z.

-

Singh-Manoux A, Marmot M. Role of socialization in explaining social inequalities in wellness. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(9):2129–33. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.070.

-

Mak HW, Coulter R, Fancourt D. Patterns of social inequality in arts and cultural participation: findings from a nationally representative sample of adults living in the United kingdom of Great U.k. and Northern Ireland. Public Heal Panor. 2020;half-dozen:55–68.

-

Lamont M, Beljean South, Clair One thousand. What is missing? Cultural processes and causal pathways to inequality. Socio Econ Rev. 2014;12(3):573–608. https://doi.org/x.1093/ser/mwu011.

-

Fancourt D, Finn South. What is the evidence on the office of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. Copenhagen; 2019. https://europepmc.org/article/NBK/nbk553773

-

Fancourt D, Aughterson H, Finn S, Walker E, Steptoe A. How leisure activities affect health: A review and multi-level theoretical framework of mechanisms of action using the lens of complex adaptive systems science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30384-9.

-

National Endowment for the Arts. How a Nation Engages With Art: Highlights from the 2012 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts. Washington, DC; 2013. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/highlights-from-2012-sppa-revised-oct-2015.pdf

-

National Endowment for the Arts. U.S. Patterns of Arts Participation: A Full Study from the 2017 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts. Washington, DC; 2019. https://world wide web.arts.gov/sites/default/files/US_Patterns_of_Arts_ParticipationRevised.pdf

-

Stallings SN, Mauldin B. Public engagement in the arts: a review of recent literature. 2016. https://world wide web.lacountyarts.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/lacac_pubenglitrev.pdf.

-

Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58(1):201–25. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212.

-

Nguyen AB, Moser R, Chou WY. Race and health profiles in the United States: an test of the social gradient through the 2009 CHIS adult survey. Public Health. 2014;128(12):1076–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2014.ten.003.

-

Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic condition, and wellness: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35(4):407–eleven. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000242.

-

Singh GK. Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969-1998. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(seven):1137–43. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1137.

-

Robinson JP. Arts participation in America: 1982–1992. 1993. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/NEA-Enquiry-Report-27.pdf.

-

Peterson RA, Hull PC, Kern RM. Age and arts participation: 1982–1997. 2000. https://world wide web.arts.gov/sites/default/files/ResearchReport42.pdf.

-

Ostrower F. The diversity of cultural participation: Findings from a national survey; 2005. https://doi.org/x.4324/9780203927502.

-

Seaman BA. Empirical Studies of Demand for the Performing Arts. In V. A. Ginsburg & D. Throsby (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture. 2006;1:415–72. https://doi.org/x.1016/S1574-0676(06)01014-three.

-

Welch 5, Kim Y. Race/ethnicity and arts participation: findings from the survey of public participation in the arts. 2010. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED519762.pdf.

-

Blume-Kohout M, Leonard SR, Novak-Leonard JL. When Going Gets Tough: Barriers and Motivations Affecting Arts Attendance. 2015. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/when-going-gets-tough-revised2.pdf.

-

Ateca-Amestoy Five, Gorostiaga A, Rossi M. Motivations and barriers to heritage date in Latin America: tangible and intangible dimensions. J Cult Econ. 2020;44(3):397–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-019-09366-z.

-

Suarez-Fernandez Southward, Prieto-Rodriguez J, Perez-Villadoniga MJ. The changing role of didactics as nosotros move from pop to highbrow culture. J Cult Econ. 2020;44(two):189–212. https://doi.org/x.1007/s10824-019-09355-two.

-

DiMaggio P, Ostrower F. Race, ethnicity and participation in the arts. Washington, D.C.; 1992. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/NEA-Inquiry-Written report-25.pdf

-

Borgonovi F. Performing arts attendance: an economic arroyo. Appl Econ. 2004;36(17):1871–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/0003684042000264010.

-

Egede LE, Walker RJ. Structural racism, social risk factors, and Covid-19 - a dangerous convergence for black Americans. Northward Engl J Med. 2020;383(12):e77. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2023616.

-

Mak HW, Coulter R, Fancourt D. Does arts and cultural date vary geographically? Show from the UK household longitudinal study. Public Health. 2020;185:119–26. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.029.

-

Fancourt D, Mak HW. What barriers practice people experience to engaging in the arts? Structural equation modelling of the relationship between individual characteristics and capabilities, opportunities, and motivations to appoint. PLoS I. 2020;15(3):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/periodical.pone.0230487.

-

Novak-Leonard JL, Brown Equally, Brown W. Beyond omnipresence: a multi-modal agreement of arts participation. 2011. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/2008-SPPA-BeyondAttendance.pdf.

-

Rabkin N, Hedberg EC. Arts education in America: what the declines mean for arts participation. 2012. https://world wide web.arts.gov/sites/default/files/2008-SPPA-ArtsLearning.pdf.

-

Jackson M-R, Herranz J, Kabwasa-Green F. Art and culture in communities: unpacking participation. Washington, DC; 2003. http://webarchive.urban.org/UploadedPDF/311006_unpacking_participation.pdf

-

Cowen T. In praise of commercial culture: Harvard University Press; 1998.

-

Novak-Leonard JL, O'Malley MK, Truong E. Minding the gap: elucidating the disconnect between arts participation metrics and arts appointment inside immigrant communities. Cult Trends. 2015;24(two):112–21. https://doi.org/ten.1080/09548963.2015.1031477.

-

Smith TW, Davern M, Freese J, Morgan Southward. General Social Surveys, 1972–2018 [machine-readable information file]: Sponsored by National Scientific discipline Foundation. NORC at the Academy of Chicago [producer and distributor]. Data accessed from the GSS Data Explorer website at gssdataexplorer.norc.org; 2019.

-

Thompson CG, Kim RS, Aloe AM, Becker BJ. Extracting the variance in flation factor and other multicollinearity diagnostics from typical regression results. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2017;39(2):81–90. https://doi.org/ten.1080/01973533.2016.1277529.

-

White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for exercise. Stat Med. 2011;30(four):377–99. https://doi.org/ten.1002/sim.4067.

-

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. 2019.

-

DiMaggio P. Gender, networks, and cultural capital. Poetics. 2004;32(two):99–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2004.02.004.

-

Christin A. Gender and highbrow cultural participation in the U.s.a.. Poetics. 2012;40(5):423–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2012.07.003.

-

Schmutz Five, Stearns East, Glennie EJ. Cultural majuscule formation in boyhood: loftier schools and the gender gap in arts activity participation. Poetics. 2016;57:27–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2016.04.003.

-

Lewis GB, Seaman BA. Sexual orientation and need for the arts. Soc Sci Q. 2004;85(3):523–38. https://doi.org/ten.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.00231.x.

-

Montgomery SS, Robinson MD. Empirical evidence of the furnishings of marriage on male person and female person attendance at sports and arts. Soc Sci Q. 2010;91(one):99–116. https://doi.org/ten.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00683.ten.

-

Semega J, Kollar M, Shrider EA, Creamer JF. Income and Poverty in the United states of america: 2019. US Census Bur Curr Popul Reports. 2020;September:60–270.

-

Dwyer C, Weston-Sementelli J, Lewis CK, Hiebert-Larson J. Why we engage: attending, creating, and performing art. 2020. https://world wide web.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Why-Nosotros-Engage-0920_0.pdf.

-

Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. In: Richardson J, editor. Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of pedagogy. New York: Greenwood Printing; 1986. p. 241–58.

-

Novak-Leonard JL, Baach P, Schultz A, Farrell B, Anderson West, Rabkin Due north. The Irresolute Landscape of Arts Participation: A Synthesis of Literature and Expert Interviews. 2014. https://doi.org/ten.6082/uchicago.1262.

-

Elpus One thousand. Music education promotes lifelong date with the arts. Psychol Music. 2018;46(2):155–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735617697508.

-

Fancourt D, Steptoe A. Cultural appointment and mental health: Does socio-economic status explicate the association? Soc Sci Med. 2019;236(Feb):112425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112425.

-

de Almeida CCR, Lima JPR, Gatto MFF. Expenditure on cultural events: preferences or opportunities? An assay of Brazilian consumer information. J Cult Econ. 2020;44(iii):451–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-019-09370-three.

-

De la Vega P, Suarez-Fernández S, Boto-García D, Prieto-Rodríguez J. Playing a play: online and live performing arts consumers profiles and the office of supply constraints. J Cult Econ. 2020;44(three):425–fifty. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-019-09367-y.

-

U.South. Demography Bureau. 2017 National Population Projections Tables 2018. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html.

-

Brown CS, Ravallion G. Inequality and the coronavirus: socioeconomic covariates of behavioral responses and viral outcomes across United states counties. 2020. http://www.nber.org/papers/w27549.

-

van Dorn A, Cooney RE, Sabin ML. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the U.s.a.. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1243–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(twenty)30893-Ten.

-

Bowleg L. Nosotros're not all in this together: on COVID-19, intersectionality, and structural inequality. Am J Public Wellness. 2020;110(7):917–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305766.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros thank Shanae Burch, Nupur Chaudhury, and David Fakunle, thought leaders on work at the intersections of the arts, disinterestedness, and public health in the United states of america, for their comments on this manuscript. We also gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the GSS study participants.

Funding

The EpiArts Lab, a National Endowment for the Arts Research Lab at the University of Florida, is supported in function by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts (1862896–38-C-20). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not stand for the views of the National Endowment for the Arts Office of Enquiry & Analysis or the National Endowment for the Arts. The National Endowment for the Arts does not guarantee the accurateness or completeness of the information included in this fabric and is non responsible for any consequences of its use. The EpiArts Lab is also supported by the University of Florida, the Pabst Steinmetz Foundation, and Bloomberg Philanthropies. DF is supported past the Wellcome Trust [205407/Z/16/Z].

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

JKB, FB, and DF designed the report. JKB conducted the assay and drafted the manuscript. JKB, FB, MEF, EP, JKS, and DF contributed to the writing, made critical revisions, and approved the terminal manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All GSS participants gave informed consent and this study has Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Florida (IRB201901792) and ethical approving from University Higher London Inquiry Ethics Committee (projection 18839/001). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant ethical guidelines and regulations, the Helsinki Declaration (2013 revision), and the General Data Protection Regulation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Boosted information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The images or other third political party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If fabric is not included in the article's Artistic Commons licence and your intended apply is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted utilise, you will demand to obtain permission direct from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Artistic Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Os, J.M., Bu, F., Fluharty, K.E. et al. Who engages in the arts in the United states? A comparison of several types of engagement using data from The Full general Social Survey. BMC Public Health 21, 1349 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11263-0

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11263-0

Keywords

- Arts

- Culture

- Social gradient

- Wellbeing

- Wellness

- The states

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-11263-0

0 Response to "2008 Household Survey of Public Participation in the Arts"

Post a Comment